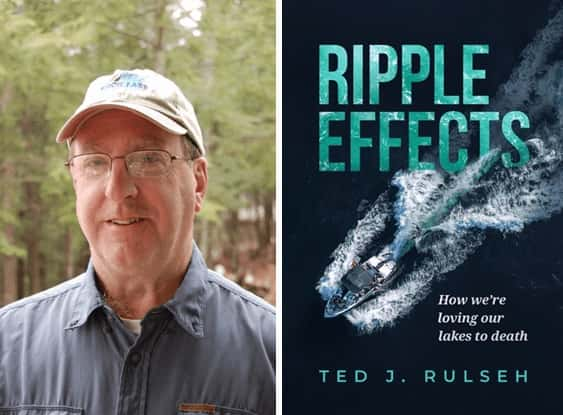

We are very excited to have Ted Rulseh speak at our Annual meeting in Little Falls on June 13. His book Ripple Effects: How We’re Loving Our Lakes to Death chronicles the reasons behind our vanishing natural shorelines and other impacts to lake life.

To whet your appetite, we think you will enjoy reading the preface. And if you haven’t got a copy of the book yet, you will have an opportunity at the Annual Meeting.

Preface

Nothing I’ve read better describes the primal attraction humans have to water than these words from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.

Say you are in the country; in some high land of lakes. Take almost any path you please, and ten to one it carries you down in a dale, and leaves you there by a pool in the stream. There is magic in it. Let the most absent-minded of men be plunged in his deepest reveries—stand that man on his legs, set his feet a-going, and he will infallibly lead you to water, if water there be in all that region.

For some of us, that water is the ocean or the Great Lakes; for some, wide rivers or rushing trout streams; and for others, like me, the clusters of bluewater jewels in the parts of North America sculpted by the glaciers. The waters differ, but the allure is the same.

To say there’s magic in it is no hyperbole. I’ve been addicted to lakes since I was eight, when I spent a weekend with my father and older brother on Duck Lake, in the big woods of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The straight, rough trunks of two majestic pines framed the sweeping lake vista from the screen porch of the cottage. Down a short path from the porch stairs, waves of tannin-stained water lapped against a beach of coarse sand sprinkled with pebbles of milky quartz. At the water’s edge, irregular mounds of brown-on-white foam quivered in the wind.

Until that weekend, I had never seen a bald eagle, stood beneath such tall trees, or heard the distant wail of a loon. The lakes near our home, amid a landscape dominated by dairy farms, were small, weedy pools, surrounded by houses and cottages, many with mowed lawns, barren of trees. At Duck Lake, white pines and spruces, maples and birches towered over the shorelines. Except for a modest log house on an island across a quarter mile of water, I could see no other structures from a vantage point on the beach. For years after that first visit, my family—Mom and Dad, four boys and four girls—took a week (sometimes two) of summer vacation at the cottage, owned by one of Dad’s coworkers. Now, six decades later, I still visit Duck Lake at least once a year, fishing from one end to the other, but always ending at sunset anchored just out from the site of that old cottage (recently demolished), above the weedy rock-and-sand bar where, as kids, we sat in rowboats and soaked bits of nightcrawler for perch, bluegills, sunfish, and bass. I’ve come to know the lake well, all eleven hundred acres, yet I still discover something new each time I go.

One type of discovery concerns me: every year it seems someone has built a large new house on the shore, in some cases sacrificing the trees for a landscape worthy of a country club golf course. Duck Lake is still far enough north, far enough from the tourist-magnet towns, to have remained suitably wild. Many other lakes are less fortunate. The traditional Northwoods allure largely persists, but each year more wooded lots are bought and built upon; each year more small cabins, in the same families for decades, are sold off and larger houses erected. Along with this trend come added stresses on the lake ecosystems, some quickly obvious, others less so: Nutrient pollution and algae blooms. Invasive species. Failing septic systems. Bigger and higher-powered boats creating wakes that can erode shorelines. A changing climate. Meanwhile, state and local government programs aimed at lake protection are, in many cases, severely understaffed and underfunded.

All this is sobering, and so is the reality that, as a lake property owner and resident, I am part of the problem. I had wanted a place on a Northwoods lake ever since those long-ago Duck Lake summers. My wife and I finally got one in 2009. We had always thought of buying an existing cottage in order to avoid contributing to the rampant buildup of lakefronts. As it turned out, we bought a vacant lot on a wooded slope above Birch Lake in northern Wisconsin’s lake-rich Oneida County, and there we built a modest two-bedroom home.

Our sensibilities being what they are, and based on what we had learned over the years from people we considered good lake stewards, we chose to tread lightly, mainly by keeping the woods of white pine, hemlock, balsam, and oak between the house and the lake fully intact. But we’re not inclined to nominate ourselves for some kind of stewardship sainthood; we have impacts on the lake by the mere fact of living where we do. In the realm of lake advocacy, there is no room to be self-satisfied.

Meanwhile, amid all the threats to our lakes, there are causes for optimism. Many lake residents have left their properties reasonably natural; long sweeps of shoreline remain wooded, especially on lakes partly within state, national, or county forests. Loons and eagles and other wildlife abound. Fishing is generally good. Water quality in most lakes is still high. There remains a vast treasure of natural bounty and scenic beauty to protect. Most important, armies of lake advocates are at work daily—in state natural resources agencies, in universities and extensions, in county and local governments, and in myriad groups such as watershed councils and lake associations—promoting sound property development practices and good lake stewardship.

Still, for someone in love since childhood with a wilder Northwoods, the trends are concerning. No one is doing damage on purpose; no malignant force is at work to degrade the lakes. No sinister industry dumps in pollutants—threats like acid rain and toxic mercury deposition from electric power plant emissions were largely cured years ago by federal and state regulation.

No, the simple truth is that we who live on the shorelines are loving our lakes to death. Like Melville’s Ishmael, we’re enchanted by water. We want our lakefront homes, our boats and boathouses, gazebos and lawns, garages and storage buildings. And if we’re not careful, we risk setting the lakes on a course for slow, steady, and possibly at some point irreversible degradation.

The fundamental reason we harm the lakes is not that we don’t care. It’s that we often fail to connect what we do on the land with what happens as a consequence to the lake—to the water’s clarity; to the fishes’ reproduction, growth, and survival; to the overall health of the lake ecosystem; to the desirability and value of the homes on the lakeshore; and to the quality of lake country life itself.

This book aims to help establish the connection. I’ve interviewed lake experts of many stripes from around the region and reviewed numerous research reports, all to understand the nature and severity of threats to our lakes, their underlying causes, and the cures available. The information can serve as a guide for how, together, we can enjoy our lakes while providing the optimum measure of protection.

There are remedies for most of what ails our lakes; many simply require changing the ways we live on and around them. Government regulation and financial support surely must play a role, but the remedies in large part depend on all of us doing the right things—one property, one home, one boat, one lake at a time.

From Ripple Effects: How We’re Loving Our Lakes to Death by Ted J. Rulseh. Reprinted by permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. © 2022 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved